Braves Hope ‘Tamahakan’ Leadership Program Gives Them Player Development Edge

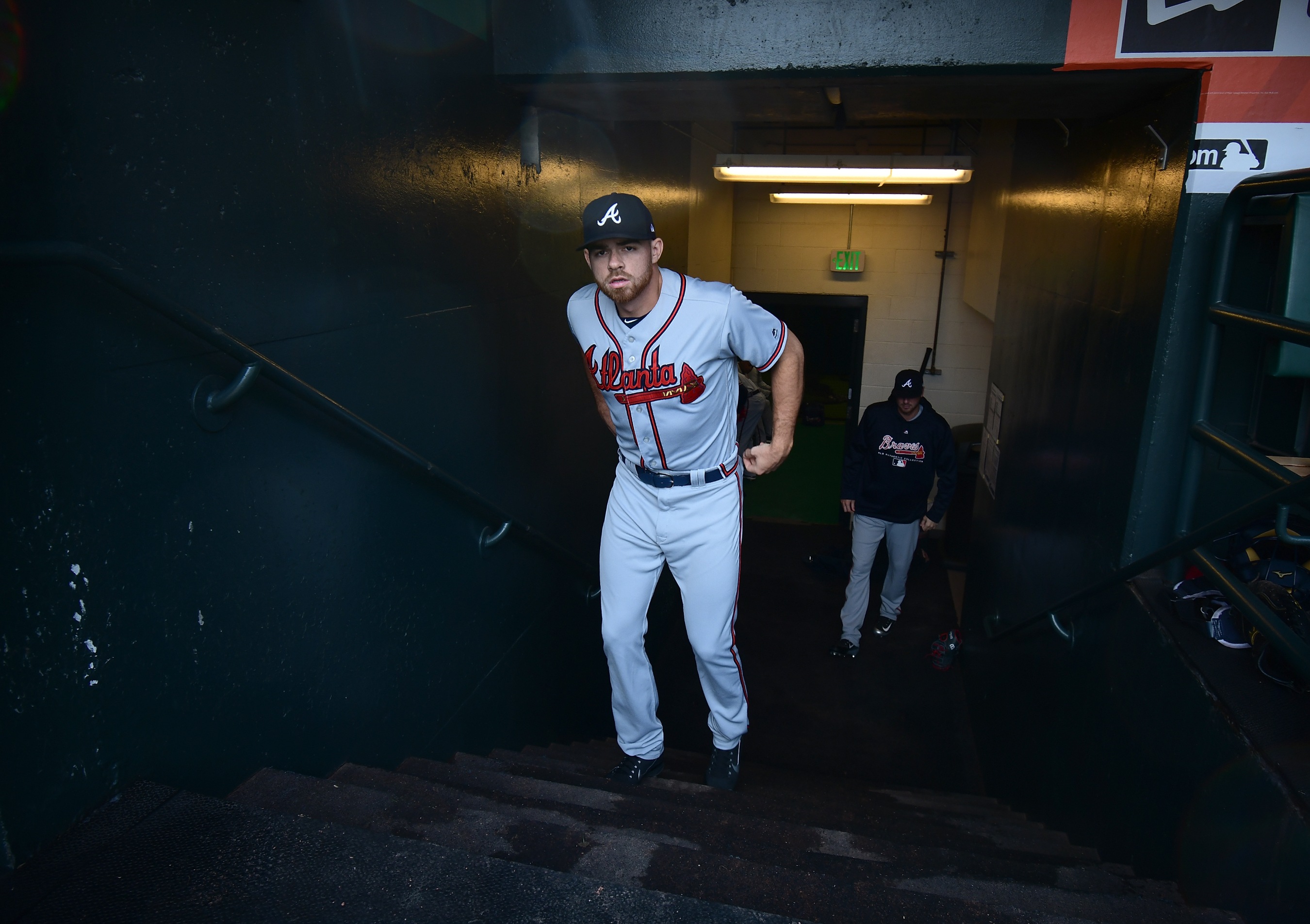

Image credit: Performance Therapist Jordan Wolf, Braves manager of minor league operations A.J. Scola, righthander Mike Soroka and righthander Ian Anderson.

From a young age, Jesse Biddle knew that he and heights did not mix. He rode a roller-coaster once as a kid and promised never to do it again. On airplanes, he wanted the aisle seat in order to avoid catching a glimpse out of the window while flying at 30,000 feet. Driving over bridges was a nerve-wracking experience.

But here he was on the first day of the Braves’ Tamahakan leadership camp, standing 60 feet up on the side of a building.

“I was the first guy down. They told me to rappel down a six-story building. The only thing keeping me from falling as my teammates holding the rope,” Biddle said.

His heart began to race, but Biddle fought through fear and found himself safely on the ground. No roller-coaster, no airplane and no bridge would ever be as frightening again.

As a baseball player, Biddle had other fears. Biddle was once a top prospect — he ranked No. 71 on the Baseball America Top 100 Prospects list heading into the 2014 season, but a concussion ruined that season, Tommy John surgery wiped out all of 2015 and a torn lat muscle ruined his 2017 season. Biddle had first reached Double-A as a prospect on his way up in 2013. Five seasons later, he was still in Double-A.

But six months after Tamahakan, Biddle made his major league debut. Much like when he was atop that building, Biddle’s heart began to race. But having faced one fear, he was ready for another. That flood of stress that he felt when he stepped onto the major league mound for the first time didn’t feel as frightening either. He ended up making 60 appearances for the Braves, striking out more than a batter per inning while posting a 3.11 ERA.

As he sees it, the two stories are related.

“Now I go out of my way to face my fear of heights,” Biddle said. “If that doesn’t translate to baseball … I had been in the minor leagues for eight seasons. I had this fear of, ‘What if I finally make it to the big leagues and I suck? What if I’m not good enough?’ I think conquering fears is one of the biggest things they were teaching us. You have to jump to find out if you can land. Being fearless in the face of fear, I took that away from it big time.

“It was a somewhat life-changing experience.”

This winter, a number of Braves prospects, coaches and front office officials will head to the third iteration of Tamahakan. It was an idea that sprung from some draft-day discussions between front office officials. At first, it was greeted warily and understandably skeptically. Now, players hope to get the call for the invitation-only event.

And in a sport where every team hopes to find whatever extra edge they can, Braves officials say they believe it has helped both in the clubhouse and on the field.

“Better people make Better Braves,” said the Braves’ manager of minor league operations A.J. Scola, who helped develop the program. “If we can make our players better people through a holistic approach, we feel like their performance will improve on the field.”

The Braves are one of the most aggressive teams in baseball pushing young players up to the majors. This year, there were five players 20 years old or younger playing in the major leagues, and four of them were Braves. In the past five seasons, there have been five pitchers who have made stars in the major leagues before their 21st birthday, and four of them pitched for Atlanta.

“The guys who run the program, we truly believe it’s a big part of why guys can go from Class A to the big leagues in six months,” Scola said.

The numbers would appear to back up what Scola is saying. Over the past few years, no team has been more successful at moving high school pitchers through the minors to the big leagues. Around baseball, teams continue to struggle to draft and develop high school pitchers. In the 2014-16 drafts, the rest of baseball drafted 77 prep pitchers in the top five rounds. Just six of them (8 percent) have reached the majors.

Over the same three drafts, the Braves picked eight prep pitchers in the top five rounds. Bryse Wilson, Mike Soroka and Kolby Allard have all made the majors, so 37.5 percent of the bRaves’ picks are big leaguers already.

If goes beyond that. Touki Toussaint, a 2014 first-round pick by the D-backs whom the Braves acquired in a trade, is also a major leaguer. Of the other five prep pitchers the Braves took over that time, Kyle Muller, Ian Anderson and Joey Wentz are well-regarded prospects.

There’s a lot of credit that can be spread around. Some goes to the Braves’ scouting department. While Soroka and Allard were first-round picks in 2015, Wilson was a fourth-round pick who was the 20th prep pitcher picked in 2016. He was the first high school player from his draft class to reach the majors. Four of the seven first-round prep pitchers from that draft have yet to get out of low Class A.

Some credit goes to the Braves’ player development department. which has pushed pitchers quickly to higher levels and has seen them respond.

“I think a lot of it is when you have guys like Dom Chiti, Dave Wallace, Jonathan Schuerholz and others (in player development),” Braves scouting director Brian Bridges said. “We know who we are handing them over to, that’s the key.”

But according to some of the players, the Braves’ Tamahakan leadership program deserves credit as well. The name derives from the Algonquin word for tomahawk.

“We always said if you are a mentally stable person when handling stress in general, whether it’s a sport or anywhere in life it will translate to the field too,” Soroka said. “If you develop those skills as a person first, they translate to baseball second. One of the goals is to make better people. Better people make better teammates.”

The idea for the Braves’ program came about during the 2016 draft. While the picks rolled by one after another, a couple of Braves front office officials began thinking out loud. They expected the Braves would continue to draft well. They believed in the team’s analytics and player development departments. But they also knew that everyone in baseball spends a lot of time and effort on scouting, analytics and player development.

“What can we do that no other team in baseball we think is doing and that we can be the best at doing?” Scola said. “How do we become the best in baseball at developing the whole player?”

Although they didn’t fully flesh it out that day, that was the beginning of the idea for the Tamahakan program. By the offseason, the Braves had set up an invitation-only program for a small group of players and a couple of front office officials with the approval of higher-ups.

“It would have been very easy for an accomplished baseball lifer like (current Braves farm director) Dom (Chiti) to shrug off such an off-the-wall concept. But his openness and growth mindset have enabled the program to be successful,” Scola said.

The first invitations were pretty vague and Soroka and his teammates arrived having little idea what they were getting into.

“We weren’t told exactly what was happening. We were somewhat confused,” Soroka said.

“But quickly those players realized that some front office officials were also going through the program, and before long the separation between player and executive blurred.

“Being there with a couple of the staff members did mean a lot because if meant they cared as well. They truly believed in it. That went a long way in showing us that they thought it could do some good,” Soroka said.

When Soroka made his major league debut this summer, his introduction to the clubhouse was smoothed by the fact that he had been minor league teammates with Ronald Acuna Jr. and a few others. He had played in spring training games with many of the veterans. But he also had gone through Tamahakan with Sean Newcomb and a few others. I got a big hug from (A.J.) Minter and Biddle,” Soroka said. “I went through Tamahakan with Minter in ’16. Obviously it’s a new clubhouse with some veteran presence, but it definitely felt like home pretty quickly.”

The Braves are not the first team to bring in leadership experts with military experience to try to help connect and share leadership and team-building experiences. The idea was to help players and other Braves staff to learn how to become better leaders and how to handle stress.

“Let’s take people in different businesses that have nothing to do with baseball,” Scola said. “Let’s talk about how to deal with conflict with peers. Let’s get our guys stressed out so they understand how they compartmentalize it. Let’s help them on and off the field.”

But after the first program was complete, everyone realized that it was also a great way to help build a cohesive team. When Biddle arrived as part of the 2017 Tamahakan class, he was surprised to find coaches were asked to do everything the players were required to do.

“We had our pitching coordinator. He was working as hard as anyone I’ve ever seen work. When you have coaches and front office people doing the same thing, no one wants to hear a 25-year-old complain about it,” Biddle said. “It was a unique bonding experience we were able to have with people you don’t normally get that close to. The guys in charge of us did such a good job making clear that no one would get treated any differently. They have the same expectation.

“For as long as I know these guys there will be unspoken bond between every coach and player who was there. I’m very grateful for the Braves for organizing it and believing in it.”

The program has now survived a changeover in leadership. General manager Alex Anthopoulos took over the reins last November and saw the value in continuing the leadership program.

Now, it’s starting to build on itself. Players hope to get invited even though it means giving up some of their offseason. Every year, more and more Braves players can call themselves Tamahakan alumni.

The Braves hope that it also helps bridge cultural divides as Spanish-speaking and English-speaking players get to connect in an intense, one-of-a-kind experience.

And now the pupils are becoming teachers. Soroka and Anderson went through the program as participants in year one. They asked if they could do it again. They were return to Tamahakn this year, but they will be doing the program as part of the staff.

“They had the opportunity to help design the program,” Scola said. “They have skin in the game. It says a lot about the players that they’ll give up a week of their offseason to do this.”

Comments are closed.